Welcome to the August 2015 edition of Righting Crime Fiction. This month, I’m continuing with the footwork techniques segment of my “Writer’s Guide to Fighting” series. After wrapping up the techniques, I’ll detail some exercises to help improve a fighter’s footwork.

DIAGONAL FRONT STEP

Moving directly forward against a retreating suspect can sometimes be risky, because your head and body remain along the same line of attack. Utilizing the diagonal front step can move you forward while taking your body out of the line of attack and creating an angle from which to deliver strikes of your own.

Additionally, the diagonal front step can be effective against a suspect who is advancing toward you. By utilizing the diagonal front step, you will be able to close the gap quicker than your suspect expected while moving your body out of the line of fire. You can simultaneously execute various types of strikes, such as a right straight knee, to help end the physical confrontation.

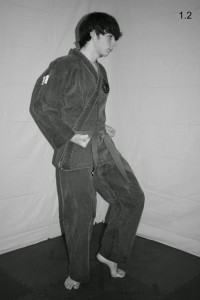

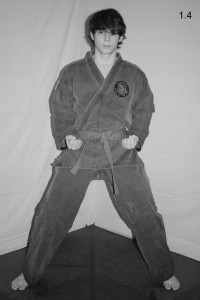

Step One: From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.64), push off with the ball of your right foot and slide your left foot about one half step forward and diagonally to the left, at about a forty-five degree angle (see Fig. 1.65).

Step Two: Quickly drag your right foot forward and diagonally the same distance the left foot traveled, which will bring you back to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.66). For a close-up of the diagonal front step leg action, see Fig. 1.67 – 1.69.

DIAGONAL BACK STEP

Moving directly rearward against an advancing suspect can sometimes be risky, because your head and body remain along the same line of attack and your suspect can move forward quicker than you can move backward. If your suspect were to reach you, he would have momentum on his side and could tackle you to the ground. Thus, it is imperative you get out of the suspect’s line of attack while positioning yourself to deliver strikes of your own that can help end the physical confrontation. The diagonal back step can help you accomplish these goals.

The diagonal back step can be even more effective when used in combination with other footwork techniques, such as pivots and side steps.

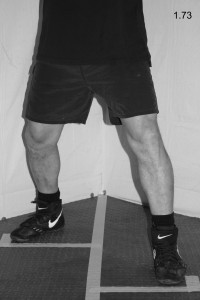

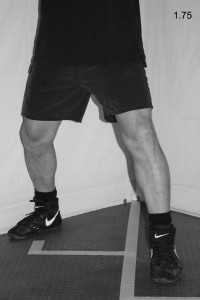

Step One: From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.70), push off with the ball of your left foot and slide your right foot about one half step rearward and diagonally to the right, at about a forty-five degree angle (see Fig. 1.71).

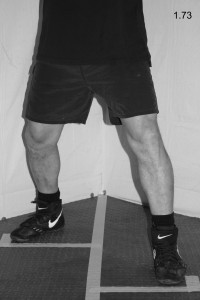

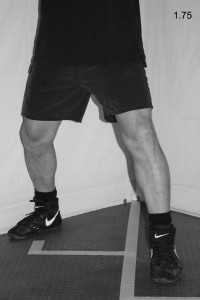

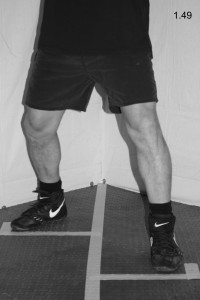

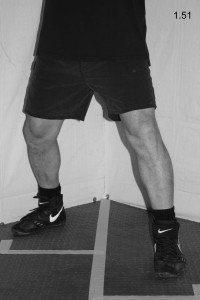

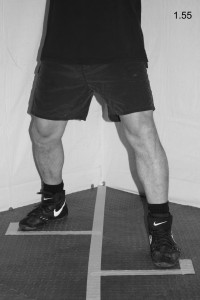

Step Two: Quickly drag your left foot rearward and diagonally the same distance the right foot traveled, which will bring you back to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.72). For a close-up of the diagonal back step leg action, see Fig. 1.73 – 1.75.

COUNTERCLOCKWISE PIVOT

The counterclockwise pivot is a technique that spins your body forward and is great for matching your suspect’s movements, evading strikes, or creating angles from which to launch your own strikes. It is also a great technique to use to keep up with a suspect who is trying to circle you to the left in an attempt to get behind you.

Your suspect’s movement will determine how far you pivot. If your suspect moved around to your immediate left, you would pivot ninety-degrees to keep him in front of you. If your suspect moved slightly to your left, you would pivot at about a forty-five degree angle to keep him in front of you, and etc.

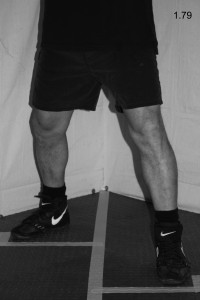

Step One: From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.76), imagine the ball of your left foot is nailed to the floor. Push off with the ball of your right foot and pivot counterclockwise on the ball of your left foot, sliding your right foot along the ground in a forward arc (see Fig. 1.77).

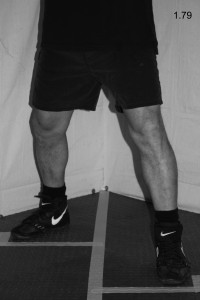

Step Two: As you pivot, your entire body should move in concert with your right foot and you should maintain your fighting stance throughout the pivot. When you end the pivot, you should be back in your fighting stance at an angle to your suspect (see Fig. 1.78). For a close-up of the counterclockwise pivot leg action, see Fig. 1.79 – 1.81.

CLOCKWISE PIVOT

The clockwise pivot is a technique that spins your body rearward and, like the counterclockwise pivot, it is great for matching your suspect’s movements, evading strikes, or creating angles from which to launch your own strikes. It is also a great technique to use to keep up with a suspect who is trying to circle you to the right in an attempt to get behind you.

Pivoting works great in combination with other footwork techniques. If you are constantly changing direction and distance, while pivoting to create angles, your suspect will have a hard time finding you in a fight. It will also help create openings for your strikes to land, which will greatly increase your chances of delivering fight-stopping strikes.

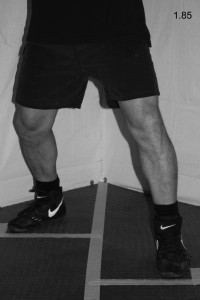

Step One: From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.82), imagine the ball of your left foot is nailed to the floor. Push off with the ball of your right foot and pivot clockwise on the ball of your left foot, sliding your left foot along the ground in a backward arc (see Fig. 1.83).

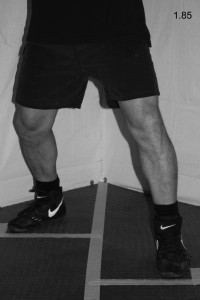

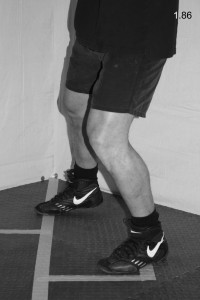

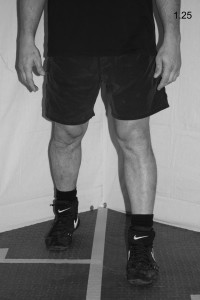

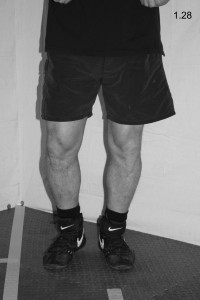

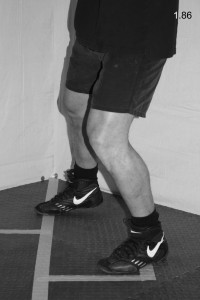

Step Two: As with the counterclockwise pivot, your entire body should move in concert with your right foot and you should maintain your fighting stance throughout the pivot. When you end the pivot, you should be back in your fighting stance at an angle to your suspect (see Fig. 1.84). For a close-up of the counterclockwise pivot leg action, see Fig. 1.85 – 1.87.

IMPROVING FOOTWORK

The best way to improve footwork is to actually practice the specific footwork techniques you will utilize during a physical confrontation, such as those listed previously in this chapter. In addition, there are specific exercises that can make you quicker on your feet, improve your balance while moving, and increase leg endurance.

PRACTICING FOOTWORK TECHNIQUES

To improve your footwork, practice each of the footwork techniques daily for a set number of repetitions. Move slowly at first and concentrate on performing each move with technical perfection. Be certain not to overstep, cross your feet, or bring your feet too close together while performing these movements. Also, remember to maintain your fighting stance while you move and remain on the balls of your feet. Once you can perform each of these techniques with ease, gradually increase your speed until you can perform them quickly and effortlessly.

At this point, you can begin combining front steps with back steps with side steps with pivoting, etc. You can perform this freestyle form of footwork for a certain number of timed sets with rest periods between each set. While moving, imagine there is a suspect in front of you who is also moving and vying for a position of advantage. After only a few weeks of perfect practice, you will notice a marked improvement in your footwork and you will feel much lighter on your feet.

SHADOW DRILL

Once you can perform the various footwork techniques in combination, you can progress to a more advanced exercise that I call the “shadow drill”. It is a reactionary drill that will teach you to instinctively react to a suspect’s movements. Much of law enforcement work is reactionary, meaning the suspect’s actions dictate what we do and when we do it. The element of surprise is on their side. Thus, it is imperative that you learn to react quickly and appropriately to a suspect’s movements. Proper footwork can quickly move you out of danger and into position to counterattack a suspect’s aggressive action. This level of proficiency can only be attained through constant, perfect repetition and the shadow drill is an excellent exercise for accomplishing this.

The shadow drill is a partner drill, but the partner does not have to necessarily be a fellow officer. It can be your neighborhood buddy, your spouse, or even your child. It has always been difficult for me to find willing training partners within my law enforcement community, so I made good use of my wife and children. Not only were they helping me develop skills that kept me safe on the job, but we were also spending quality and fun time together. Contrary to what many think, self-defense training does not have to be boring. Utilizing our imagination and creativity, we can stay motivated while developing those skills that are pertinent to our street survival.

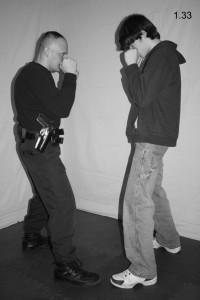

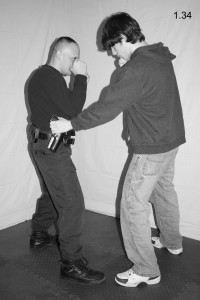

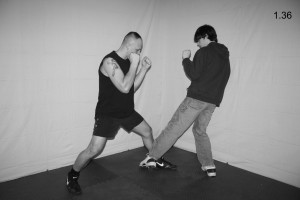

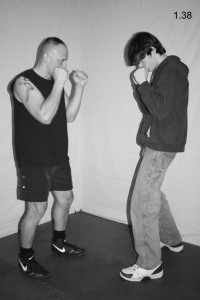

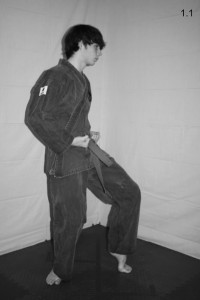

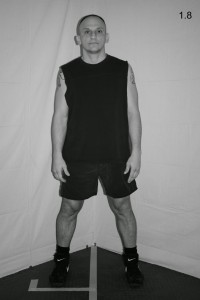

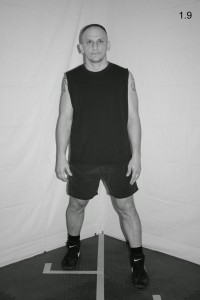

Step One: Begin in your fighting stance in front of a partner (see Fig. 1.88).

Step Two: Have your partner begin moving toward you, away from you, to your right, to your left, circling you, etc. Instruct them to move slowly at first. As your partner moves, mirror his or her movement by utilizing correct footwork technique. If your partner moves toward you, perform a back step (see Fig. 1.89). If your partner moves to your right, perform a right side step (see Fig. 1.90). And so on. Try to stick to your partner like a shadow. As you become more and more proficient, have your partner move faster and faster. Before long, you will feel as comfortable doing this drill as you do walking around in your everyday life.

SKIPPING ROPE

Another excellent exercise for improving footwork is skipping rope. This can be a difficult exercise to perform at first. However, once you become accustomed to it, it will greatly improve your foot speed and coordination. It will also build endurance in your calf muscles and this can be important if a fight lasts an extended period of time.

There are various types and styles of ropes to consider, from the heavier ropes made for strength building to the lighter ropes made for speed. There are no wrong or right answers here, just a matter of personal preference. My personal preference is the rubber rope designed for speed, since my goal is to improve my footwork speed and endurance.

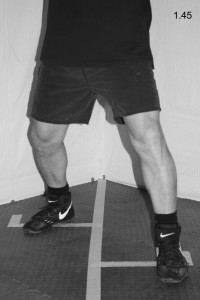

Once you have decided on what type of rope to go with, you need to determine the correct length. Do this by stepping on the center of the rope with both feet and raising the handles up toward your armpits. If each handle reaches the respective armpit, the rope is the correct size (see Fig. 1.91). If they do not reach the armpits, you need a longer rope. If they go beyond the armpits, you need to shorten the rope.

Step One: Begin standing in front of the rope while holding the handles firmly in your hands. Your hands should be held about waist high at your sides (see Fig. 1.92).

Step Two: Rotate your wrists and arms back, up, and over in an exaggerated arc to make the rope travel up and over the back of your head (see Fig. 1.93). As the rope travels down along the front of your body, jump over it and continue the rotation (see Fig. 1.94). Once it gains momentum, you will use your wrists to keep the rotation going.

Tip One: Make sure to jump only once for each revolution and only jump high enough to clear the rope, which should be about two to three inches. You might have a tendency to double-bounce and jump too high at first, but with practice you can alleviate this habit.

Tip Two: As you skip rope, concentrate on keeping your chin tucked, as it will help to engrain this invaluable defensive technique into your mind.

At first, you can begin skipping rope by performing a predetermined number of repetitions, such as fifty. As you become more proficient, progress to skipping rope for a predetermined period of time.

There are several variations to skipping rope. One is to simply jump straight up and down as the rope crosses under your feet, which gives your calf muscles an intense workout. A second variation is to jog in place as you skip over the rope. A third variation is to skip for a predetermined number of repetitions on one leg, and then switch to the other leg. As with any exercise program, mix up your routine to make it challenging and fun.

CONCLUSION

This will conclude the August segment of Righting Crime Fiction. If any of you have any questions or comments or suggested topics, feel free to contact me at rightingcrimefiction@gmail.com and I will reply as soon as I can.

Until next time, write, rewrite, and get it right!

BJ Bourg is the author of JAMES 516 (Amber Quill Press, 2014), THE SEVENTH TAKING (Amber Quill Press, 2015), and HOLLOW CRIB (Five Star-Gale-Cengage, 2016).

Copyright © 2015 by BJ Bourg. All rights reserved.