Welcome to the July 2015 edition of Righting Crime Fiction. This month, I’m continuing with the “Writer’s Guide to Fighting” series and moving into footwork techniques. It might not seem like much, but footwork is as important as knowing how to block a punch. In fact, it should be considered your first line of defense in an attack. Next would be head movement and blocking.

Note: Again, I am addressing your law enforcement characters directly, because it is easier and more concise than constantly referring to them as “your characters”, “s/he”, “them”, etc.

IMPORTANCE OF FOOTWORK

The best way to avoid an attack is to not be there, which makes footwork an integral part of your defense system. Whether you are in an unarmed fight or a shootout, you will be harder to hit as a moving target than a stationary one. However, there are right and wrong ways to move during a fight, and I will detail the proper footwork techniques to utilize during a physical confrontation. This is an important section, because you could get hurt if you move the wrong way.

If Drew Brees explained in detail how to throw a perfect spiral, it would not make you a better quarterback. You would have to actually get up and practice those techniques. Similarly, merely reading these instructions will not improve your footwork. You must practice them until you can perform them effortlessly and without thought.

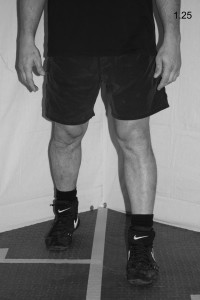

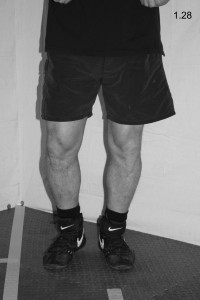

Proper movement during a fight differs greatly from everyday movement. All of our lives we have been moving around by putting one foot in front of the other, crossing our feet as we go (see Fig. 1.25 and 1.26). This is not the proper way to move in a fight. Crossing your feet in a fight should be viewed as a cardinal sin. The only way to keep from committing this sin is to spend countless hours practicing proper footwork.

You will basically need to learn how to walk all over again. If you have never practiced this type of footwork, it will go against what seems natural to you. You might feel awkward at first, but within a few sessions you will find yourself moving quicker and more gracefully. With enough practice, the techniques will become second nature and moving during a fight will be as natural to you as walking down the street. It takes time and dedication to reach and maintain this level of proficiency, but it is a small price to pay for your safety.

As with the fighting stance, the footwork techniques listed in this book derive from boxing. A boxer’s footwork is more practical for law enforcement work than traditional martial arts footwork. The biggest problem with martial arts footwork is that they violate the rule of not crossing your feet. If you have ever studied traditional martial arts and have performed katas (patterns of movement that some claim will improve your fighting skills), you have violated this cardinal rule of crossing your feet (see Fig. 1.27 – 1.29). Every time you perform these katas, you are actually developing and reinforcing bad habits that could prove deadly in a real fight.

Boxers are taught not to cross their feet in a fight because it will compromise their balance and leave them susceptible to knockdowns (see Fig. 1.30 – 1.32). This is especially important for law enforcement officers, because if you get knocked down by a suspect you are at his or her mercy, and most of these suspects are not very compassionate.

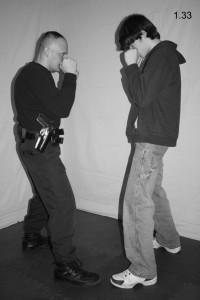

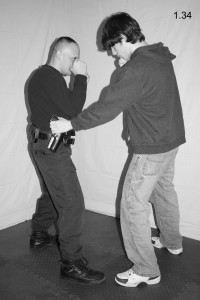

Additionally, if you cross your feet during a fight your firearm side will be toward the suspect and it could be easily grabbed (see Fig. 1.33 and 1.34).

KEYS TO EFFECTIVE FOOTWORK

- Always remember that when moving during a fight, the foot closest to the intended direction moves first. As an example, if you wanted to move forward, your lead foot would move first. If you wanted to move laterally to the right, your right foot would move first. And so on.

- As you move, do not lift your feet off the ground. Instead, slide the ball of your feet lightly and explosively along the ground in the intended direction, moving one foot at a time. Never hop into the air where both feet leave the ground at the same time. If both feet are in the air, you are no longer grounded and you could easily be taken down. Being grounded is crucial to remaining balanced.

- Maintain your balance, head position, and hand position throughout the footwork techniques. As you move, your suspect could be punching and kicking at you, so it is imperative that your chin remain tucked, your hands up, and you stay balanced.

- Keep your movements short, quick, and smooth. Each foot should travel the same distance as the other. For example, if you move your left foot eight inches forward, you should also move your right foot eight inches forward. This will ensure you always return to the proper fighting stance.

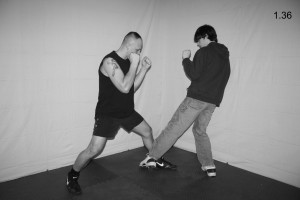

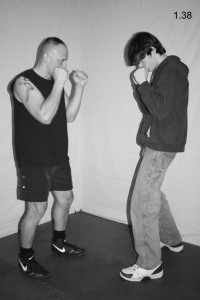

- Do not move your feet too far apart. If you slide one foot too far from the other when moving, your stance will be too wide and you will be susceptible to leg sweeps (see Fig. 1.35 – 1.37). Likewise, you should not allow your feet to get too close together, because you could leave yourself open to double-leg takedowns (see Fig. 1.38 and 1.39).

FOOTWORK TECHNIQUES

I will cover eight footwork techniques that will enable you to maneuver effectively during a fight with a suspect.

Front Step

If your suspect is moving away from you or if you need to move closer to your suspect to execute combinations, you will perform the front step. A good strike to execute in conjunction with a front step is the left jab.

- From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.40), push off with the ball of your right foot and slide your left foot about one half step forward, which should be about six to twelve inches (see Fig. 1.41).

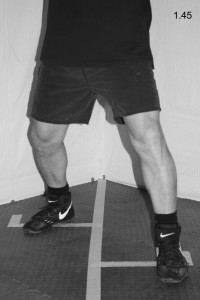

- Quickly drag your right foot forward the same distance the left foot traveled, which will return you to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.42). As an example, if the left foot travels six inches, the right foot should also travel six inches. As mentioned in Key Two, the ball of your right foot should drag the ground lightly as it moves forward. For a close-up of the front step leg action, see Fig. 1.43 – 1.45.

Back Step

If your suspect is advancing toward you, you can perform the back step to create distance between yourself and the suspect. You can also perform the back step if you need to create distance to allow you to perform a particular strike. For instance, if you are in punching range and you wish to execute a kick, you can perform a quick back step to give you the room to execute the kick.

Additionally, be mindful that it is not always good to move directly rearward as a suspect advances toward you. You will want to create angles and pivot to get out of the way, so you will need to utilize the back step in conjunction with other footwork techniques.

- From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.46), push off with the ball of your left foot and slide your right foot about one half step rearward, which should be about six to twelve inches (see Fig. 1.47).

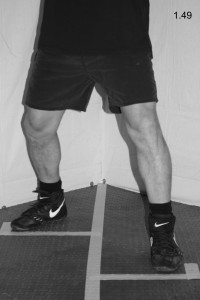

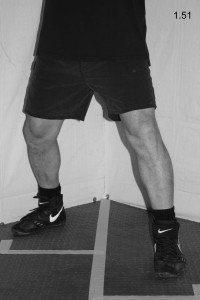

- Quickly drag your left foot rearward the same distance the right foot traveled, which will return you to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.48). For a close-up of the back step leg action, see Fig. 1.49 – 1.51.

Right Side Step

If your suspect moves to your right, you can mirror him by performing the right side step. If he tries to circle around to your right to get behind you, you can also use the right side step to cut him off. If this happens, you must be prepared to execute strikes immediately upon taking that step. A good strike to use in cutting off your suspect to the right is the right hook punch or the right Muay Thai kick.

You can also use the right side step to avoid attacks and create varying angles of attack. For instance, if your suspect executes a straight kick or punch, you could perform a right side step and then immediately execute a strike of your own before he realizes you are “gone”.

- From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.52), push off with the ball of your left foot and slide your right foot about one half step to the right, which should be about six to twelve inches (see Fig. 1.53).

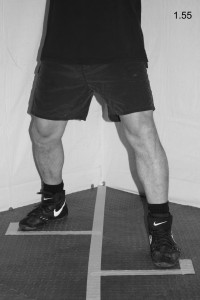

- Quickly drag your left foot laterally the same distance the right foot traveled, which will bring you back to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.54). For a close-up of the right side step leg action, see Fig. 1.55 – 1.57.

Left Side Step

If your suspect moves to your left, you can mirror him by performing the left side step. If he tries to circle around to your left to get behind you, you can use the left side step to cut him off. Like with the right side step, you must be prepared to execute strikes immediately upon taking the side step. A good strike to use in cutting off your suspect to the left is the left hook punch or the left Muay Thai kick.

Like the right side step, you can use the left side step to avoid attacks and create varying angles of attack. Since your body is positioned at a forty-five degree angle to your suspect, you will create different angles by moving left than you would by moving right. You should use this to your advantage.

- From your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.58), push off with the ball of your right foot and slide your left foot about one half step to the left, about six to twelve inches (see Fig. 1.59).

- Quickly drag your right foot laterally the same distance the left foot traveled, which will bring you back to your fighting stance (see Fig. 1.60). For a close-up of the left side step leg action, see Fig. 1.61 – 1.63.

CONCLUSION

That will wrap up the July segment of Righting Crime Fiction. If any of you have any questions or comments or suggested topics, feel free to contact me at rightingcrimefiction@gmail.com and I will reply as soon as I can.

Until next time, write, rewrite, and get it right!

BJ Bourg is the author of JAMES 516 (Amber Quill Press, 2014), THE SEVENTH TAKING (Amber Quill Press, 2015), and HOLLOW CRIB (Five Star-Gale-Cengage, 2016).

Copyright © 2015 by BJ Bourg. All rights reserved.