Welcome to the May 2015 edition of Righting Crime Fiction. This month begins a series of blog posts about self-defense—one of my favorite subjects. In order for writers to create characters who can fight, they must learn how to fight.

INTRODUCTION

I’m a self-made fighter. At the age of about twelve, I began researching and studying every martial arts and full-contact fighting system/style I could find. I learned the techniques, perfected them, and then applied them in full-contact sparring sessions. I retained what worked and discarded what didn’t, developing my own fighting style using the best of each system I studied. Basically, I was mixing martial arts long before it became cool. Along the way, I joined a karate school so I could have regular sparring partners and even competed in several open karate tournaments, taking first place in all of them. The point system structure of tournament karate does little to prepare someone for brutal combat, and I eventually quit doing it. When a boxing gym opened up near where I lived, I joined and became a professional boxer (2002 through 2005) at the age of 31. I hung up my gloves in late 2005, because training at the boxing gym every night took me away from my children too much, and they were my priority. Currently, I continue to remain in fighting condition and I train my son, who is an amateur boxer, and my daughter, whose interest in fighting can be traced back to watching Ronda Rousey fight (she practically begged me to preorder Rousey’s MY FIGHT / YOUR FIGHT).

In 1990, I embarked upon a career in law enforcement and went through the police academy, where I was exposed to law enforcement’s defensive tactics. I found many of the techniques to be impractical. During my career, I’ve been attacked by many suspects while trying to arrest them. I’ve found myself facing individual suspects of various skill levels, multiple suspects at one time, and suspects armed with various types of weapons (firearms, knives, bats, etc.), and I’ve succeeded in apprehending all of these subjects with very minor or no injuries. Unfortunately, my success can’t be attributed to my training in the police academy. Rather, I survived those encounters because I’d made a lifestyle choice as a child—and that was to train everyday as a full-contact fighter in order to defend myself and those I loved from anyone who might try to do us harm.

Later, in 2003, I went to work as a fulltime police academy instructor and became certified as a defensive tactics instructor and instructor-trainer. I quickly realized they were teaching the same techniques I’d learned in 1990, many of which were impractical and some even dangerous to employ. When I started teaching law enforcement officers how to defend themselves, I taught them how to survive a full-contact fight, because law enforcement is a full-contact profession. Through those teachings, I coined the phrase “The Full-Contact Officer”, and I subsequently wrote a series of related articles that appeared in Law and Order Magazine.

In the upcoming series of blog posts—which will be based upon applied knowledge and not supposition or mere training—I’m going to share some of these fighting techniques and principles to help writers 1) develop characters who can take care of themselves and 2) write convincing fight scenes. Additionally, writers can use the information provided to develop their own self-defense skills

BALANCE

Balance is an essential component of self-defense. Whether interviewing subjects or making arrests, your cop characters must always maintain a position of balance while keeping their firearms away from the suspects. When cops lose their balance, bad things happen. Some of those bad things could include them being slammed to the ground, knocked out or disarmed, none of which are conducive to a long and healthy lifestyle.

IMPORTANCE OF A PROPER FIGHTING STANCE

Before a house can be built, a sound foundation must be constructed. Similarly, before your characters can learn other aspects of fighting, they must first develop a solid fighting stance from which to launch their attacks and from which to thwart the attacks of their suspects. While a wider and deeper stance offers greater balance, it restricts mobility; and while a narrow stance offers greater mobility, it doesn’t provide sufficient balance. A solid fighting stance is one that offers an even blend of balance and mobility.

While the stances of most law enforcement self-defense systems are based upon traditional martial arts, the fighting stance I recommend derives from boxing. As a student of both, traditional martial arts and boxing, I learned very early in my life/law enforcement career that the boxing stance is more applicable to law enforcement work than those of the traditional martial arts.

The various martial arts stances, such as the front stance, back stance, straddle stance, and cat stance all lack the even mixture of balance and mobility that are necessary for your characters to survive a physical confrontation. By virtue of body positioning, they’re static and limit options, thus they’re not effective for real-world situations. They might be fine for performing kata or point sparring, where there are specific rules that all participants must follow, but they’re not appropriate for realistic combat.

Here are some of the reasons these stances aren’t suitable for practical law enforcement defense:

Back Stance: The back stance requires officers to place about two-thirds of their body weight on their rear leg by positioning their hips over the leg (see Fig. 1.1). This greatly hampers mobility and leaves them vulnerable to a number of attacks, especially takedowns. It also inhibits them from delivering effective power kicks with the rear leg.

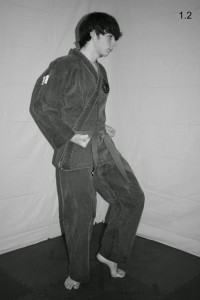

Cat Stance: The cat stance is similar to the back stance, but there is more weight on the rear leg and the legs are closer together (see Fig. 1.2). The problems are also similar to those of the back stance.

Front Stance: The front stance requires officers to place the majority of their body weight on the lead leg by positioning their hips forward, while the rear leg is straight and extends behind their body (see Fig. 1.3). This also hampers mobility, and makes it difficult for them to quickly defend against a kick to the lead leg.

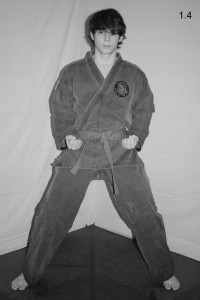

Straddle Stance: The straddle stance calls for an unnaturally wide stance (see Fig. 1.4). If the suspect is to one side of them, officers wouldn’t be able to launch an effective attack with the rear leg and arm from that stance, because the rear leg and arm would be positioned too far to the rear, and the stance would greatly hamper their mobility and prevent them from being able to launch kicking attacks. Also, the lead leg could easily be swept or broken with a roundhouse kick to the lower leg. If the suspect is in front of them, the “squared-up” position would leave them vulnerable to being easily knocked backward or taken to the ground.

STANCES FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT

I advocate two stances for law enforcement officers: the ready stance and the fighting stance (I’ll detail the fighting stance in the June segment of Righting Crime Fiction). Officers will perform most of their duties in the ready stance. I call it the ready stance because officers must constantly remain vigilant as they perform their duties—always ready for the unexpected. When a suspect becomes aggressive, your officer would then switch to the fighting stance. Some law enforcement trainers and administrators prefer to refrain from using the term “fighting” as it relates to an officer’s stance, choosing to call it a “defensive” stance instead. While I understand the logic behind this, I unapologetically call it a fighting stance. I want officers to realize that when they drop into the fighting stance, they are absolutely in a fight—potentially a fight for their lives.

READY STANCE

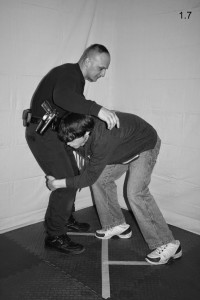

Whether writing citations, interviewing witnesses, or ordering a hamburger, your officers should always remain in the ready stance. They should never stand flatfooted and squared-up to anyone while performing their duties—especially when wearing their firearm—as it would place their gun closer to the suspect’s reach (see Fig. 1.5). Standing flatfooted will also make them susceptible to being pushed backwards (see Fig. 1.6) or taken to the ground (see Fig. 1.7).

Note: For the purposes of this blog, I will explain and demonstrate each technique for right-handed officers facing right-handed suspects, as most people are right-handed. If you’re writing a left-handed character (commonly referred to as the “southpaw” position in fighting), simply reverse the hand/foot/body positions.

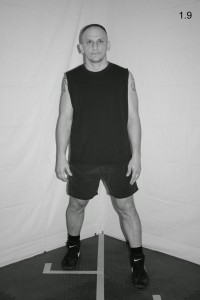

Step 1: To assume the ready stance, officers begin by standing with their feet parallel and shoulder-width apart (see Fig. 1.8). They should remain relaxed with their head centered above their midsection.

Step 2: They would then take a half step directly forward with their left leg, maintaining the shoulder-width distance between their feet (see Fig. 1.9). Their left leg would become the lead leg, while their right leg would be the rear leg. The step will have turned their body at a slight angle to their imaginary suspect, putting the lead leg closest to the suspect and the rear leg farthest. This simple maneuver places their right hip, which is where their firearm is located, farther from the suspect’s reach.

Step 3: They would then turn the toes of their right foot slightly outward, while keeping the toes of their left foot pointed at their suspect (see Fig. 1.10).

Step 4: They should keep their knees “soft” and loose while distributing their weight evenly on both feet. They shouldn’t bear their weight on their heels, as this would greatly limit their mobility.

Step 5: They would raise their hands above their waist, at chest-level, and keep them out in front of their body (see Fig. 1.11). This will enable them to more readily defend a sudden and unexpected attack. It is also a natural position for their hands to be while taking notes, writing citations, or merely motioning while talking.

Tip 1: Don’t have your officers clasp their hands together or interlock their fingers, as the suspect could grab and trap both of their hands with one of his, allowing him to pound on your officers with the other (see Fig. 1.12).

NOTE: I heard one law enforcement officer tell a group of writers that real cops use “teepee” hands when talking to people—um, only if they want to get knocked into next week and wake up not knowing their name. If you’re describing an interview scene and you want your officer to be tactically proficient, don’t have her interlock her fingers or use “teepee” hands. She can simply gesture with her hands as she talks, keeping them above her waist.

Tip 2: Your officers can distribute their weight evenly on both feet by simply keeping their head above centerline (centered above their groin area).

CONCLUSION

Well, that will wrap up the May segment of Righting Crime Fiction. If any of you have any questions or comments or suggested topics, feel free to contact me and I will reply as soon as I can.

Until next time, write, rewrite, and get it right!

BJ Bourg is the author of JAMES 516 (Amber Quill Press, 2014), THE SEVENTH TAKING (Amber Quill Press, 2015), and HOLLOW CRIB (Five Star-Gale-Cengage, 2016).

©BJ Bourg 2015