Welcome to the November 2014 edition of Righting Crime Fiction. As I mentioned last month, I’ll discuss how your fictional detective can use firearms evidence to solve crimes that involve guns. If you know next to nothing about firearms and you want to write a murder mystery that involves a gun, it might seem a daunting task. However, with just a basic understanding of the types of evidence that firearms can leave behind and how to link those pieces of evidence to each other and to your bad guy, you’ll be able to easily write convincing scenes involving guns and ammunition.

I’m going to break this up into a few blog posts, because it can turn into “information overload” if I’m not careful. For this month’s edition, I’ll discuss what a spent casing can immediately tell your detective at the scene and I’ll demonstrate how shell casings are deposited at crime scenes.

SPENT SHELL CASINGS TALK

If someone fired a single shot into the air on a desolate road at night and then disappeared, leaving behind nothing but one spent shell casing, that single shell casing will offer your detective some valuable information. The most obvious and immediately helpful thing it will tell her is the caliber of the bullet, and, from that one piece of information, she can deduce a lot.

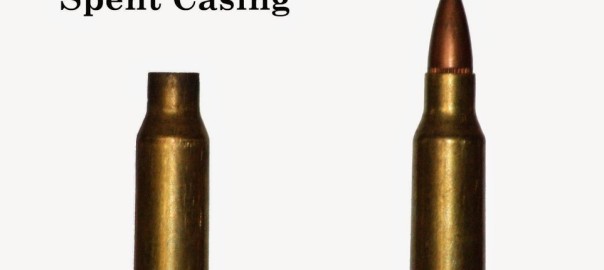

Spent Casing vs. Live Round

First, the reason it’s “obvious” is because most detectives can recognize the more commonly used calibers by sight. If they can’t recognize the caliber by sight, all they need to do is look at the face of the casing, where the caliber information will have been stamped onto it during the manufacturing of the casing. The above bullet and casing are .223 caliber.

Second, the reason it’s “immediately helpful” is because she can instantly rule out every weapon that could not have fired that round. If she didn’t know the caliber of the firearm used, every gun in the world could be a potential suspect. Armed with the caliber information, she could then narrow down her search to only the firearms that could’ve fired that round.

Let’s imagine she locates a spent .357 magnum shell casing on that lonely road. She can then rule out every type of semi-automatic handgun (except for those few that can fire a .357 magnum bullet, such as the Mark XIX Desert Eagle), every type of long gun (except for those few that can fire a .357 magnum bullet, such as the Marlin Model 1894), and every type of revolver that is not chambered in .357 magnum. She can now concentrate her efforts on the finite number of guns that could have possibly fired the bullet, rather than on every type of gun ever made.

TRANSFERING INTO FICTION

Writing spent shell casings into your story is easy to do and it can help you plant clues for your readers along the way. If you mention early in your story that a spent nine millimeter shell casing was located at the crime scene, every person you mention thereafter who owns a gun capable of firing nine millimeter bullets could be a possible suspect.

If you’ve been a writer for five minutes, you know we’re supposed to “show” rather than “tell”. Thus, I’m not simply going to “tell” you how easy it is to write spent shell casings into your story—I’m going to “show” you.

Here’s an excerpt from my current work in progress:

I scanned the immediate area and spotted two spent shell casings on the floor just inside the door.

See? It’s that easy. How do we let our readers know the caliber of the casings? Here’s another excerpt later in the same chapter:

Susan crept along the living room floor toward the hallway and called out when she found another spent casing against the baseboard of the back wall. “That makes four.”

“Are they all nine millimeters?” I asked.

“Yeah.” Susan’s brow furrowed. “How’d you know it would be here?”

Now, what happens if your detective locates two different types of spent shell casings at the scene, such as five nine millimeter casings and six .357 magnum casings? This could mean that there were two shooters or that one shooter had two guns. You can experiment with this to add some degrees of difficulty to your story and make it harder for your detective to figure out “whodunit”.

IT’S NOT MAGIC

Casings don’t magically appear at a crime scene. Some action has to take place for the casing to leave the firearm and end up on the scene. If you fire a semi-automatic or fully automatic weapon, the action of pulling the trigger would be enough to eject the casings, because the recoil-action from some weapons (Glock handgun, Beretta handgun) and the gas action of others (AR-15 rifle, AK-47 rifle) will automatically strip the spent casing from the chamber and “spit” it out.

Colt AR-15 .223 Semi-Automatic Rifle

Romarm/Cugir AK47 7.62×39 Semi-Automatic Rifle

I went out to the range the other day and made a video to demonstrate how a semi-automatic firearm deposits spent casings at the scene. It depicts me firing a few rounds at regular speed, one round at slow speed (so you can watch how the pistol works), and then I fire a couple more rounds until the slide locks back. I discussed in a previous post how the slide locks back on an empty magazine on certain pistols—well, here it is in action:

Live Fire – Semi-Automatic Pistol

Did you notice the flashes of copper-colored metal flying in the air above me each time I’d shoot? Those were the shell casings. I’ll discuss in a future segment what the location of casings at the scene can tell your fictional detectives.

In other types of firearms, some manual action has to take place in order to eject the shell casing. A few different types of actions include pump-action (Benellli Nova 12 gauge shotgun), lever-action (Mossberg 30-30 rifle), and bolt-action (Accuracy International Model AE .308 sniper rifle). In order to leave a spent casing at the crime scene, your bad guy would have to fire a round and then manipulate the action. In addition to ejecting a spent casing, this action would also push a fresh (live) round into the chamber.

Benelli Nova 12 Gauge Shotgun

Here’s a video of me working the pump action on my Benelli (it’s a sound that can strike fear in the hearts of anyone who recognizes it, especially if you’re a boy knocking on your girlfriend’s window late at night):

“Pumping” a Shotgun

Accuracy International Model AE .308 Sniper Rifle

Here’s a video of me bolting my Accuracy International sniper rifle:

“Bolting” a Sniper Rifle

Revolvers have a repeating action. As your bad guy pulls the trigger, the action of cocking the hammer, rotating the cylinder, and dropping the hammer is repeated until all of the live rounds are fired. The spent casings remain in the individual chambers until your bad guy reloads.

Keep this in mind: if your fictional detective finds casings that were fired from a revolver at the scene, it usually indicates the shooter reloaded at the scene. I’ve only witnessed this once. A man killed another man and then reloaded his revolver when he saw headlights approaching his location. It turned out to be a police officer. The suspect fired on the officer and, in the exchange of gunfire, the suspect was killed.

Smith and Wesson .44 Magnum Revolver

WORKING VARIOUS ACTIONS INTO FICTION

How does this information transfer to fiction? Consider this excerpt from my short story SNIPER’S CHOICE (Static Movement, August 2009), where I detail a sniper manipulating the bolt on his rifle:

The instructor began the countdown. When he said, “Fire!”, I dropped to the ground and pulled the butt of the sniper rifle snug into my shoulder. When the crosshairs locked on the lemon at one hundred yards, I squeezed off the shot. It exploded. My body went into autopilot. I bolted a fresh round and took out the next target. My hand was like a machine. I fired until my rifle was empty and my targets were only a misty memory.

I didn’t detail every step of the bolt-action process, because it’s not necessary and would be too technical. With the few words, I bolted a fresh round, I show readers that something has to happen to get a live round into the chamber. Instead of repeating that phrase four times, I try to paint a picture to let readers know the sniper fired multiple rounds in rapid succession by simply writing, My hand was like a machine. I fired until my rifle was empty.

CONCLUSION

That’ll wrap up Righting Crime Fiction for November. I’ll continue the discussion about shell casings in December. Until then, write, rewrite, and get it right!

BJ Bourg is the author of JAMES 516 (Amber Quill Press, 2014), THE SEVENTH TAKING (Amber Quill Press, 2015), and HOLLOW CRIB (Five Star-Gale-Cengage, 2016).

©BJ Bourg 2014

©BJ Bourg 2014