Handguns come in many different shapes, sizes, brands, models, and calibers, but they can nearly all be categorized into two main groups: revolvers and semi-automatics. Bear in mind there are some handguns that don’t fall into either of these categories, such as the Mare’s Leg (a really cool piece of firepower), which is considered a lever-action handgun.

My son shooting his Mare’s Leg (Wait—did you really think it was a female horse’s leg???)

For the purposes of this blog, I’m going to focus on revolvers and semi-automatic handguns, with this month’s primary focus being on revolvers.

REVOLVER NOMENCLATURE

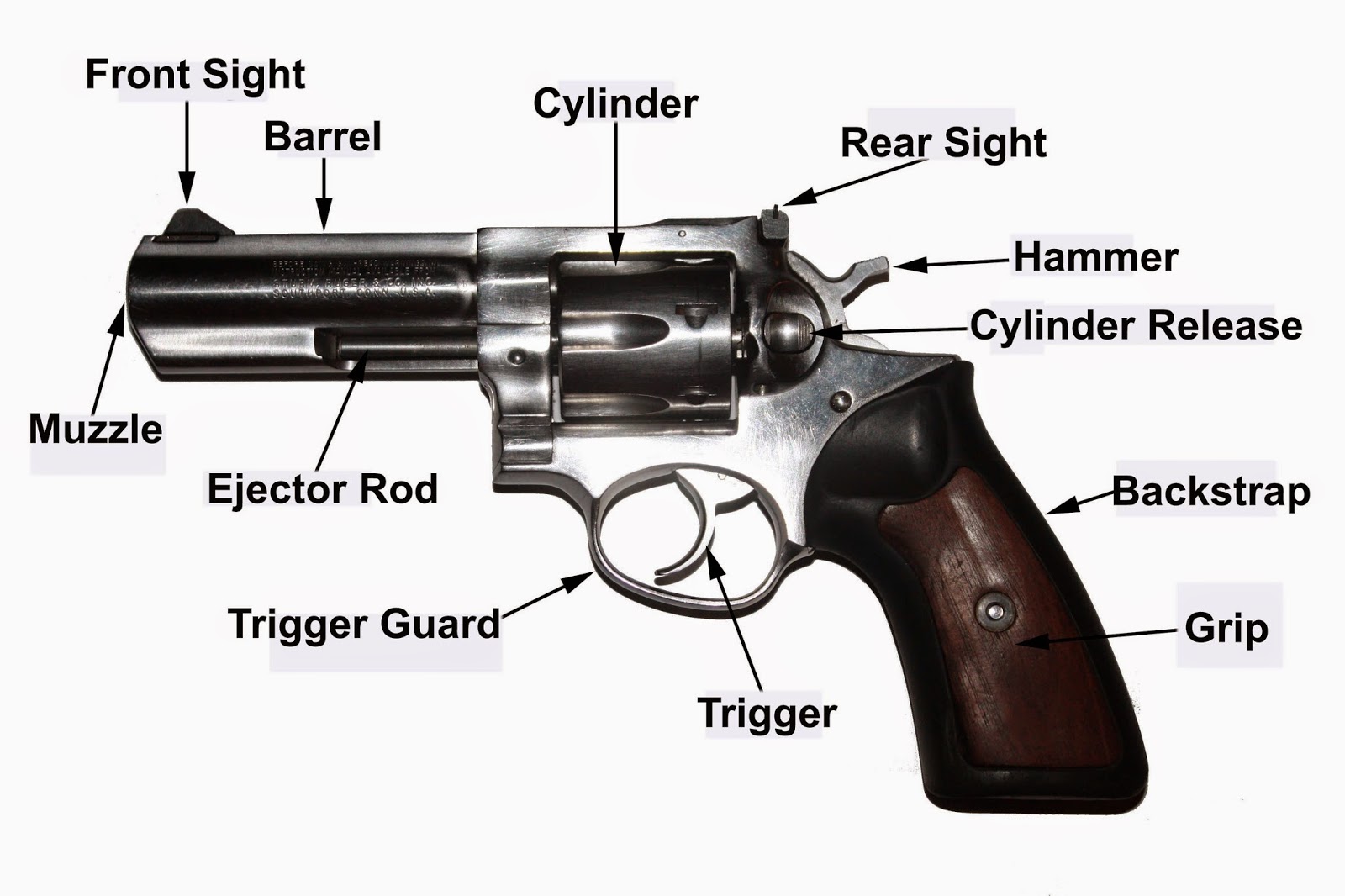

Before I dive too far into this subject, we need to familiarize ourselves with the parts of a revolver. I have created two diagrams to assist us in accomplishing this goal. The first is a side view of a Ruger GP100 .357 magnum (my first duty weapon) with the cylinder closed. The second is a view from the backside of the same revolver with the cylinder open, exposing the empty chambers.

Side view, Ruger GP100, parts listed

Rear view, Ruger GP100, open cylinder, parts listed

NOTE: Police cadets are required to know this information and are actually tested on it in the police academy.

REVOLVERS

A revolver (also called a “wheel gun”) is a handgun with a revolving cylinder that contains multiple chambers for housing bullets. Most revolvers have six chambers (hence, the name “six shooter”), making them capable of firing six shots continuously before having to be reloaded. As a writer, you don’t want your hero firing fifteen shots from a revolver that only holds six bullets. If you need him to fire fifteen shots before reloading, then you might consider putting a semi-automatic pistol in his hand (to be discussed in next month’s segment). Whatever you do, make sure you count your hero’s shots during the gunfight, so you know when he needs to reload. You might also want to make him run out of bullets at a most inopportune time in the battle (which would probably make him hate you), so it would be important to track the shots fired.

While I’m on this subject, I have to vent. It really annoys me when I watch a movie and see a person fire a gun until it empties, and then throw it away. It’s not a tube of toothpaste! It’s reusable—I promise!

While most revolvers are six-shooters, there are some that are capable of firing fewer than six bullets (the five-shot Smith and Wesson 642) and some that are capable of firing more (the seven-shot Nagant M1895).

Nagant M1895

The cylinders on some revolvers rotate clockwise and others rotate counterclockwise. For instance, the Ruger GP100 rotates counterclockwise, while the Nagant M1895 rotates clockwise. There are also different ways to access the chambers of the cylinders for loading and unloading. There are fixed cylinders (1875 Outlaw), top-break cylinders (Webley Mk VI), and swing-out cylinders (Ruger GP 100). Most modern-day revolvers come with swing-out cylinders, so I will demonstrate how to load these types of revolvers toward the end of this blog post.

1875 Outlaw (My 2012 Christmas present from my son and daughter.)

As a writer, if you specify the exact brand name and model of the revolver you place in your heroin’s hand, be certain to research that particular handgun to ensure you are providing accurate information with regard to the number of shots, rotation direction of the cylinder, caliber, etc. You don’t want her “swinging out” a cylinder on an 1875 Outlaw.

DOUBLE-ACTION VERSUS SINGLE-ACTION REVOLVERS

The difference between single-action and double-action is simply the function of the trigger. With a double-action revolver, the trigger performs two functions: it cocks the hammer and then releases it. With a single-action revolver, pulling the trigger only performs one function: it releases the hammer. It is important to note that the hammer on a single-action revolver must be manually cocked before pulling the trigger. Thus, if you have your hero “pull the trigger” on a single-action revolver before cocking it, he will be shot first.

Now, a double-action revolver can be fired single-action (simply cock the hammer before firing) or double-action, but a single-action revolver can only be fired single-action. Not fair, I know, but I don’t make the rules—I just pass them on.

I have produced two short videos: one demonstrating what it looks like to fire a revolver double-action and the other demonstrating what it looks like to fire a revolver single-action. I dry-fired the weapons, which means I pulled the trigger on an empty chamber, so there won’t be a loud “bang” when the hammer falls.

IMPORTANT NOTE: I’ve never claimed to be a professional video producer, so if the quality of the videos I put here seem poor, just blame my wife. She had nothing to do with producing the videos, but y’all can blame her anyway.

Double-Action Revolver

Single-Action Revolver

CYLINDERS

Earlier I mentioned that the revolver has a revolving cylinder. The cylinder revolves (or rotates) when the hammer is cocked (either by cocking the hammer manually on a single-action revolver or by pulling the trigger on a double-action revolver—as seen in the above two video clips), and this places a fresh cartridge under the hammer/firing pin. Keep in mind that a fully loaded revolver will have a live round under the hammer, but when the hammer is cocked, that live round rotates one position over and the second live round moves in its place to be fired. Thus, the round directly under the hammer of a fully loaded revolver will be fired last.

Why is this important? If the bad girl in your story places one bullet in the cylinder and closes the cylinder with the bullet directly under the hammer/firing pin, her victim will laugh when she pulls the trigger and nothing happens. In order to make that single bullet count on a revolver whose cylinder rotates counterclockwise, she would have to place it in the chamber immediately to the right of the hammer/firing pin. That way, when she pulls the trigger, the cylinder will rotate until the bullet is directly under the hammer/firing pin, and it will drop her victim as intended. (Who’s laughing now?) If she is using a revolver whose cylinder rotates clockwise, she simply puts the bullet in the chamber immediately to the left of the hammer/firing pin.

DO REVOLVERS HAVE SAFETIES?

Way back in the day, some gunfighters would keep the chamber under the hammer of their revolver empty for safety reasons, because the gun could go off if it were dropped and the hammer/firing pin made contact with the bullet’s primer. Some of those old revolvers, like the single-action 1875 Outlaw, had a three-stage hammer, meaning you could cock the hammer to three different positions. The first stage (or cocked position—also called a safety notch) served as a safety, as it kept the firing pin, from being in close contact with the bullet’s primer. The second stage (or cocked position) released the cylinder, allowing it to spin freely (in one direction—clockwise) for loading. The third stage (or cocked position) was the fully cocked position, readying the revolver for firing.

Three-Stage Hammer, 1875 Outlaw

Modern-day revolvers are equipped with internal safeties that prohibit the firing pin from making contact with the bullet’s primer if the handgun were ever dropped. The only way the firing pin can make contact with the bullet’s primer is if the trigger is fully depressed, thus deactivating the internal safety. Even if the hammer is cocked and it slams forward when dropped, the bullet will not go off because of the internal safety.

Some firing pins are attached to the hammer of the revolver (1875 Outlaw) and some are not, as in the case of the Ruger GP100. The Ruger GP100 (and other Rugers) has a unique internal safety mechanism called a “transfer bar”. There’s a rounded-out dimple in the hammer that lines up with the back end of the firing pin, so that if the hammer falls, nothing happens. In order for the gun to fire, the transfer bar has to be engaged, and this only happens if the trigger if fully depressed.

Ruger’s Transfer Bar

Why does this matter to you, the writer? First, you don’t want to have your character drop a modern-day revolver and it accidentally discharge and shoot his big toe off, because anyone with a little knowledge of firearms will cry foul. Second, you can use this information to your heroin’s advantage. If your bad guy tells her he dropped his revolver and it accidentally went off and shot his boss in the back of the head seven times, she’ll know it’s not true. Lastly, and most importantly, you DO NOT want your character flipping the revolver’s safety switch on or off, because a revolver doesn’t have a manual safety.

LOADING A REVOLVER WITH A SWING-OUT CYLINDER

One of the only reasons not to bring a revolver to a gunfight is the amount of time it takes to reload. With practice and utilizing the proper techniques, you can become pretty proficient at reloading a revolver, but it takes a lot of time and dedication, as well as continual training. Ever heard the old adage, “if you don’t use it, you lose it”? That holds true with the use of firearms, as well, because marksmanship is a perishable skill. While there are a couple of helpful tools that can decrease the time it takes to reload a revolver, such as a speed strip and a speed loader, it still takes some effort to develop the muscle memory necessary to reload it smoothly and without thought.

I will describe the steps necessary for a right-handed shooter to load a revolver, and that will be followed by two video clips demonstrating how it’s done. The first clip will depict me loading my revolver without an aid and the second will depict me loading my revolver with a speed loader.

Step One: Holding the revolver in your right hand, ensure that the muzzle is pointed in a safe direction.

Step Two: Press or slide (forward or rearward, depending on the type of revolver you own) the cylinder release button with your right thumb and use your left middle and ring fingers to push the cylinder open.

Step Three: Transfer the revolver to your left hand and, pointing the muzzle at the ground, hold it there while inserting bullets into the chambers with your right hand. It is best to handle two bullets at a time. As you insert bullets into the chambers, use your left thumb, left middle finger, and left ring finger to rotate the cylinder in a clockwise direction to expose the remaining empty chambers.

Step Four: Once all chambers are loaded, use the left thumb to push the cylinder closed, and use the left thumb, left middle finger, and left ring finger to rotate the cylinder until it locks in place.

Step Five: Reestablish a proper grip with your right hand.

Coincidentally, as I write this very line, I’m watching a movie on Netflix where a firearms instructor is teaching a rape victim how to shoot a revolver. He unloaded the revolver by opening the cylinder, lifting it in front of him with his right hand, and slapping the ejector rod with the palm of his left hand. He then reloaded the revolver by holding it in his right hand and placing one bullet at a time into the chamber with his left hand as the cylinder hung free. He didn’t exercise economy of motion and had poor control over the revolver, which wastes precious time when you’re trying to reload under pressure.

Loading Revolver

Loading Revolver, Speed Loader

Next, I will describe the steps necessary to unload a revolver, and that will be followed by a video clip demonstrating the proper way to unload a revolver.

Step One: Holding the revolver in your right hand, point the muzzle in a safe direction.

Step Two: Press or slide (forward or rearward, depending on the type of revolver you own) the cylinder release button with your right thumb and use your left middle and ring fingers to push the cylinder open.

Step Three: Transfer the revolver to your left hand. Pointing the muzzle upward, use your left thumb to fully depress the ejector rod, which will dump the empty casings to the ground.

Step Four:Visually inspect the chambers to be certain they are fully unloaded.

Unloading Revolver

Well, that sums up the September segment of Righting Crime Fiction. While my primary target audience is crime fiction writers, I do hope the information on this blog will be helpful to all writers. I imagine even romance writers kill off bad lovers from time to time, am I right?

Next month’s segment will most likely deal with semi-automatic handguns, unless I receive requests for a subject I just can’t pass up. In future posts, I plan to cover such topics as ballistics, crime scene investigations, interviews and interrogations, evidence collection, unarmed combat (for those who write fight scenes), sniper deployment, etc.

In the meantime, write, rewrite, and get it right!

BJ Bourg is the author of JAMES 516 (Amber Quill Press, 2014), THE SEVENTH TAKING (Amber Quill Press, 2015), and HOLLOW CRIB (Five Star-Gale-Cengage, 2016).

©BJ Bourg 2014

©BJ Bourg 2014